Posted January 08, 2024

By Byron King

Welcome to Earth, the Mining Planet

“In the next 25 years, mankind will have to produce the same amount of copper as humanity has dug from the earth in the past 5,000 years.”

The person who said this is a serious, credible guy. He’s a well-spoken, well-regarded mining company executive who holds a doctorate in geology from a topflight university. He has worked in both industry and academia for over 35 years. And he was paraphrasing a conclusion from a report by the National Mining Association, an industry trade group.

In essence, per the speaker and the trade group he cited, for the world to do what many leaders and talking heads say they want to do, we’re going to have to turn Earth into a mining planet, like in one of those science fiction movies.

Not a movie: Bingam Canyon, Utah copper mine from space. NASA Landsat.

Well, it’s a safe bet that nobody is going to dig up the entire globe. No way. But stating the issue helps to illustrate a massive problem that’s fast unfolding.

That is, there aren’t enough resources coming from the world’s mines and mills to match the dreams of people who want to drive their version of change, if not social and economic upheaval.

We’ll expand more on this in a moment. It’s worth discussing and understanding just to help illustrate the craziness of modern politics. And it will definitely affect the way you live. While on the upside, it’s investable.

So, let’s (forgive the pun) dig into this…

First, let’s be clear. No serious mining executives anywhere, ever, in their right mind believe for even one minute that we’re going to turn Earth into a mining planet.

You want a mining planet? Watch the 1992 movie “Alien 3.” (Alas, it’s pretty campy; not exactly up to snuff in an otherwise iconic movie franchise.)

Indeed, as much or more than anyone else, mining people understand limitations on resource development. That is, when it comes to building a mine, many people will say no. And precious few can (or will) ever say yes.

But the central point here is that the world is using more and more minerals and metals every day, especially copper, with even more demand in years to come. Copper is hot, as are many more metals and downstream materials. In fact, there’s an entire periodic table of items in growing demand.

The question is, where to get all of what the world will need.

Native, elemental copper and cuprite, Altai Krai, Russia. BWK collection.

Here’s one way to illustrate the point. You’ve heard of Tesla, of course, and its electric vehicles (EVs). And you’ve also probably heard that General Motors, Ford, Volkswagen and a host of other carmakers plan to phase out almost all internal combustion engines (ICE) over the next 10 to 15 years and transform their product lines to EVs.

In other articles I’ve discussed how EVs use about three or four times as much copper per car as an ICE vehicle, in the range of several hundred pounds each. More wiring, more copper in the motors, more copper in the batteries, etc. And multiply that by tens of millions, which is the scope of annual automobile output; globally, over 100 million vehicles per year. It’s literally billions of pounds of copper.

Okay, carmakers can say whatever they want. And they’ll do what they can do. But if the world auto industry goes electric even just partially the way that big guys are planning, requirements for related minerals and metals — copper, lithium, nickel, rare earths (REs) etc. — will more than double in the next decade.

Hold that thought: “double.”

Now, let’s go a step further. Because if the world goes to an extensive buildout of renewable energy — solar and wind, mostly — in just the way that Western governments have announced to date (the deep-green Biden administration comes to mind), then requirements for those same related minerals and metals will more than quadruple within 15 years.

Hold that thought: “quadruple.”

And perhaps you’ve heard of plans for complete decarbonization of the global energy system. No more coal. Phase out most oil and even natural gas. And do it all by 2050. Yes, many people actually say things like that. (It’s really dumb, but they say it anyhow.)

Well, to decarbonize the world economy and electrify pretty much everything will require well over six times the current global output of minerals and downstream metals; those same elements like copper, nickel, lithium, REs, etc.

Hold that thought: “over six times.”

Basically, per the automakers, or per the greenies in the Biden administration, or per the world-changing world-improvers, humanity is going to require more than two, four or even six times what already comes out of the world’s mines and mills.

Hmm… Two; four; six… That’s one hell of a lot of stuff. And it all must happen soon, as in starting right now.

All this futuristic new energy transition tech is over and above what we already see – as in, NOW – with, say, Chinese-made solar panels and wind machines unloaded from Chinese-flagged ships at Chinese-run ports like Long Beach. And it will carry on over the next three or four decades until America reaches that clean, glorious, electrified future that the arm-wavers promise.

Ideally, of course, and in a more perfect world, geologists would quickly discover vast, new ore bodies. And companies would quickly build multiple versions of, say, Escondida, Chile, the world’s largest copper mine.

Escondida, Chile — world’s largest copper mine. Courtesy BHP.

Umm… Wait a minute. You see where this is all going, right? Find and build a bunch more Escondida mines? And do it pronto? No, it doesn’t work that way. Because it cannot work that way. And it won’t work that way. Not. Gonna. Happen.

In the past decade, all across the world, mineral exploration budgets in general have been on a downswing. Discoveries are few and far between. Environmental regulations have increased. Water is always a fight, either to obtain it in the first place or to clean it up and discharge it after use.

Oh, and there are just not enough trained, experienced people who know how to build mines. And so on.

Meanwhile, people who live near potential copper mines (and much else in mineral districts) are, often as not, unenthusiastic about being displaced from their lands and homes, even when offered a job as a truck driver or water quality technician.

And everywhere, governments stand with the proverbial hand out, ready to impose new taxes, fees and regulations on every mining project because, to borrow a line from the old bank robber Willie Sutton, “that’s where the money is.”

Even when everything works properly, you’re looking at time spans like 10, 15, 20 and more years to get a large mine up and running. This past winter, I visited one Arizona copper project that was “discovered” in 1983 (based on reconnaissance geology performed 40 years earlier during World War II) and which finally became a working mine in about 2012, a mere 29 years.

So no, there’s nothing fast or easy about building mines, no matter how important the minerals and downstream metals and materials may be, such as this beautiful specimen of lead-silver ore.

Galena – lead-silver ore, from Dalengorsk, Russia. BWK collection.

As you may discern by now, I spend a lot of time following metals and mining. The good news is that more and more people – industry, government, finance, academe – are beginning to worry about how to (literally) keep the lights on. The bad news is that the U.S. is not doing much of what must happen to keep those lights burning.

Obviously, it’s nice when you flick a switch and things work. But the lights and appliances only work if there’s electricity in the wires, which came over more wires from a power plant. And that plant is a mass of complex machinery, powered by some energy source.

Somewhere upstream, the energy fuel made it to that power plant; coal on a train, gas in a pipeline, uranium in the form of rods inside shielded tubes. You can see where this goes, right?

But per the people who want to change the world, we’re going to somehow go to solar and wind to run the country. We’ll fundamentally change the energy landscape, figuratively and literally, and then rewire the continent. And they mean to do it big time and fast, with fairy dust and magic most likely because that’s the only way this can work.

Yeah, right. Somehow, all the lights will still work. Your household appliances, too. Plus, the load on the system will power an EV or two in your garage. Totally reliable. Piece of cake, eh?

You might think that, with ambitions like what we see from the governing class and elite influencers, a big, powerful, complex industrial country like the U.S. would be in control of its economic destiny. But you would be wrong.

I’m not talking about mere tie-ups and waiting lines at U.S. ports, where mostly foreign-owned and flagged cargo ships discharge their foreign-made cargos.

No, America’s problem is far more basic than how long it takes for a 40-foot container of manufactured goods to land, clear customs and make its way to your nearby Walmart or Target, let alone to the new solar or wind farm out in the deserts of Arizona, if not a backyard near you.

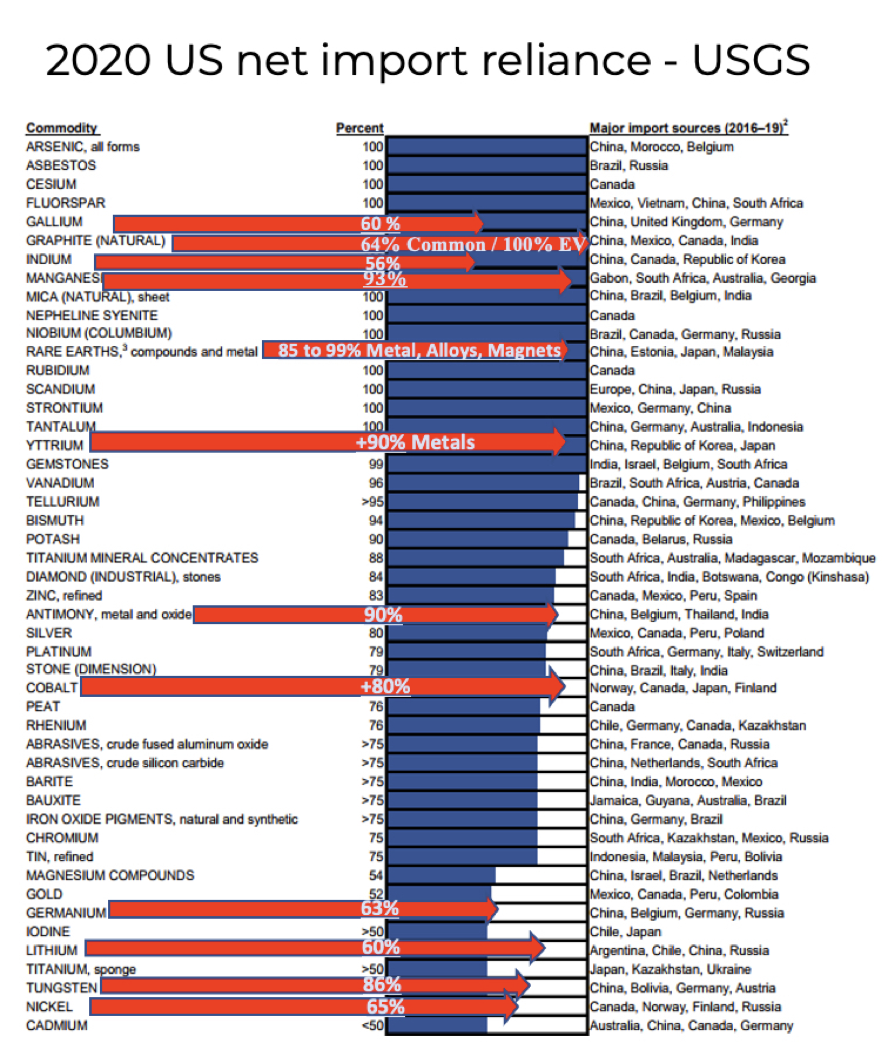

One massive national problem in all of this is embodied in the following chart, courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). It lists the degree of U.S. import reliance on foreign sources for a long list of basic materials. And it should make you very worried. Indeed, read it and weep.

Helpfully, all those red lines indicate critical materials that come to the U.S. from Chinese sources (“red,” get it?). And the red lines show the percentage of Chinese supply, usually quite significant.

It all gets back to converting Earth into a mining planet. Because the world (certainly the U.S. economy) runs on a foundation of basic materials, most of which the U.S. does not produce, or does not produce in great quantity. So where do we get them? From other people, usually far away.

And sure, we live in a world of trade. The U.S. economy fits into the global economy and one of the great features of that is the ability to buy things our country needs from other nations.

But right now, we’re on the cusp of massive change, grounded (excuse the term) in overturning the existing energy system and requiring explosive growth in demand for critical minerals, metals and related materials.

Where will it all go in the future?

Well, it’s a rocky road ahead. But again… it’s investable. And we’ll discuss it more in future articles. For now, just look at the scale of what’s happening. Let it all soak in.

Thank you for subscribing and reading.

How Others’ Incompetence Costs You Big-Time

Posted January 17, 2024

By Byron King

Turning Empty Cubicles Into Houses

Posted January 15, 2024

By Zach Scheidt

"Boring AI": Overlooked Opportunity From CES 2024

Posted January 12, 2024

By Zach Scheidt

All Sizzle, No Steak: On the Hunt for Profitable Tech

Posted January 05, 2024

By Zach Scheidt

2024 Election: Here’s What Happens

Posted January 03, 2024

By Jim Rickards